As a young attorney working for the International Criminal Court in The Hague, Netherlands, Kate Finley found it striking when Thomas Lubanga Dyilo, a Congolese militia leader who was found guilty of conscripting child soldiers, was sentenced to just 14 years in prison. It made an impression on Finley, who was fresh out of Stanford Law School.

“I thought, ‘Wow, you can be convicted of the most serious crimes — war crimes, crimes against humanity — and do less time than you would for a drug distribution case in America,’” said Finley, now a clinical associate professor and director of the Frank J. Remington Center at University of Wisconsin Law School.

After five years with the International Criminal Court, Finley decided that she could make a bigger impact back home as a public defender. Her next career stops took her to the Maryland Office of the Public Defender, the Vera Institute of Justice and Rutgers Law School before she joined UW Law in 2019. She felt an immediate connection to the Remington Center’s mission.

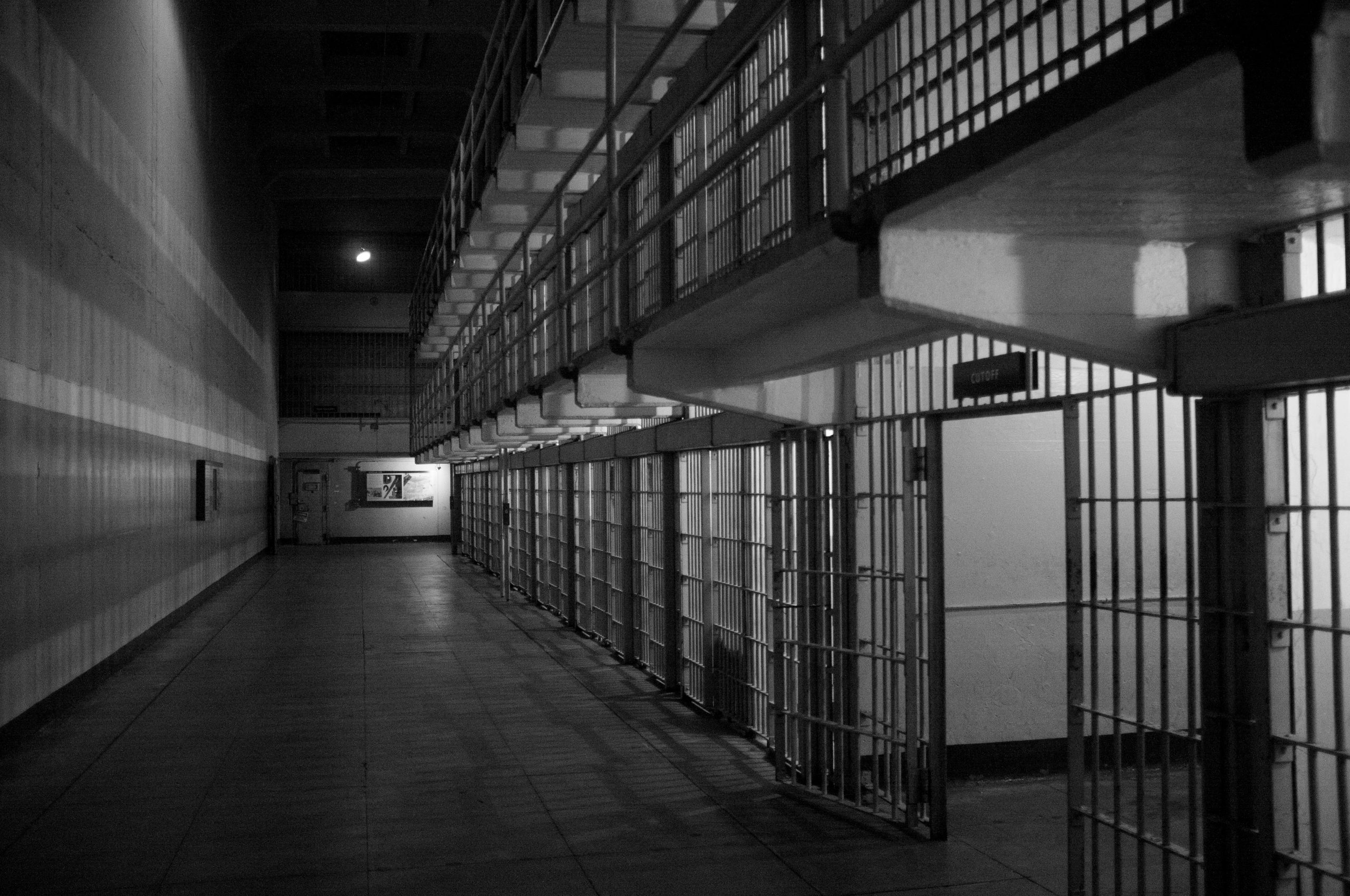

“The Remington Center is so unique because it’s been around for 50-odd years and exists specifically to serve people who have already been sentenced,” Finley noted. “We have seven different legal clinics where students work with incarcerated people. I don’t know of any other law school that has that many prison-based clinics.”

At any given time, the center’s clinics work on approximately 100 cases. Finley directs the Second Look Clinic, which helps clients who are serving excessive prison sentences. The clinic is especially needed in Wisconsin, she said.

“During the ‘tough on crime’ ’90s, judges across the country were sending people away for life or greater than natural life sentences, and in Wisconsin, the sentences for young Black men in Milwaukee were some of the most extreme,” she said. “The Second Look Clinic represents a number of people who received these extraordinary sentences and assists them in seeking release, via advocacy and litigation.”

Some of the clinic’s clients were teenagers when they were convicted decades ago and won’t be eligible for parole for many decades, if ever, despite excellent prison conduct, records of program completion and very low risk ratings.

Among the clinic’s recent successes is the release of an elderly client who was freed after serving 53 years and who has since returned to the Law School to share his experiences as a jailhouse lawyer with students and to attend a Federalist Society debate. Another client, who was convicted at age 14 and then released after 25 years, found a full-time job and is working toward his bachelor’s degree.

“Second look work can be challenging, but it is so powerful for students to be able to stand with their clients as they jointly seek a legal path to release — and even more moving to see a client get released and begin the process of rebuilding and making amends, and living a meaningful, law-abiding life,” Finley said.

Finley also conducts research in the area of second look release, including a forthcoming article on the use of prison evidence. Second look statutes in many states direct judges deciding release petitions to consider prison conduct reports, programming reports and certificates as evidence of whether an incarcerated individual is rehabilitated, but these statutes largely ignore the realities of prison, Finley noted.

“During the ‘tough on crime’ ’90s, judges across the country were sending people away for life or greater than natural life sentences, and in Wisconsin, the sentences for young Black men in Milwaukee were some of the most extreme.” – Kate Finley

To start, many prisons no longer offer programs that could be used to demonstrate rehabilitation. And prosecutors opposing second look release have argued that minor infractions, such as putting ice in a pitcher instead of a cup or having an extra piece of cheese on a sandwich, are evidence that an incarcerated individual won’t abide by the law if released and should therefore stay in prison.

“This research is directly inspired by the work of the Second Look Clinic,” Finley said.

Finley is proud to continue the Remington Center’s legacy of providing impactful learning experiences for students, including those who don’t plan to pursue criminal law as a career.

“Remington Center students have so many amazing opportunities to do really impactful client-centered legal work,” she said.

“Students might present an oral argument, negotiate with prosecutors about an innocence case, coordinate a restorative dialogue or draft motions to modify a sentence. They get the extraordinary experience of representing a person who may have no right to legal counsel otherwise and then providing them with really high-quality representation and — in some cases — students might be there to meet a client at the door to the prison and, almost literally, walk them home.”

By Nicole Sweeney Etter